Silence can often yield more power than words. It can be a very good tactic to convey the message more powerfully than even any formal announcement. Australia, India, Japan, and the United States seem to be practicing this by not mentioning the China factor as one of the rationales for the ongoing 27th edition of the Malabar exercise off the Sydney coast.

The 4-nation exercise began on August 11 and will conclude on August 21. Australia is hosting it for the first time.

Vice-Admiral Karl Thomas, commander of the US Navy’s Seventh Fleet, said at a news conference on August 10 in Sydney that the exercise was “not pointed towards any one country” and would improve the ability of the four forces to work with one another.

“The deterrence that our four nations provide as we operate together as a Quad is a foundation for all the other nations operating in this region,” he added.

According to Vice-Admiral Dinesh Tripathi of the Indian Navy, who is leading the Indian contingent, “The four nations, the four democracies can work together in the maritime domain, and that can send some signals around the world,” Tripathi said.

“The Indo-Pacific is very important to us,” said the Australian fleet commander, Rear-Admiral Christopher Smith, adding, “We understand people have the ambition to continue to grow and develop… but it’s about transparency.”

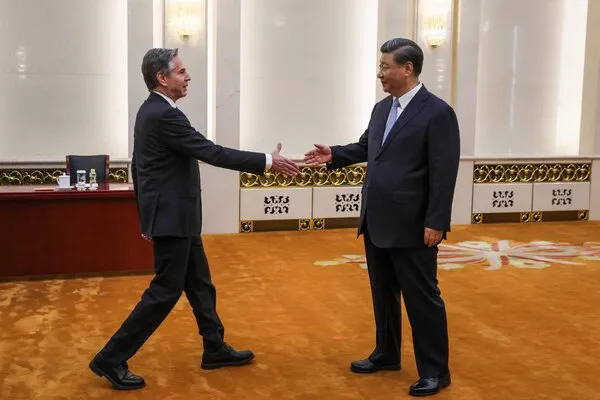

As can be seen, China was not mentioned by any of the participating Admirals. Some argue that this could be intentional, with India hosting the G-20 summit in New Delhi (September 9 and 10), where all the heads of the governments, including President Xi Jinping, are expected to meet. Besides, Modi is also to come across Xi in South Africa during the 15th BRIC summit (Brazil, Russia, India, China) on August 22-24 at Johannesburg.

Here, the theory is that the possible meetings of the leaders from Australia, India, Japan, and the US with Xi at the G-20 summit and the Modi-Xi parleys in South Africa have necessitated the lowering of the tenor of anti-China rhetoric.

This also explains, it is said, why India could not keep the Australian invitation to participate in the ‘Talisman Sabre’ military drill, which was hosted by Australia from July 22 to August 4, involving 34,000 military personnel from 13 nations, including Australia, Japan, Canada, France, Germany, the United States, and the United Kingdom. This multilateral exercise involved forces across the sea, land, air, cyber, and space.

However, such a theory does not explain why the Quad-4 did not postpone the Malabar exercise to invite or elicit appreciation from Xi, a known critic of the drill. On the contrary, the intensity of nature and range of exercise this time is said to be at a higher level compared to its previous editions.

Malabar 2023 is being conducted in two phases. The Harbour- Phase involves wide-ranging activities such as cross-deck visits, professional exchanges, sports fixtures, and several interactions for planning and conduct of the Sea Phase.

The Sea- Phase includes various complex and high-intensity exercises in all three domains of warfare, encompassing anti-surface, anti-air, and anti-submarine exercises, including live weapon firing drills.

According to the Indian Navy, the exercise provides it an opportunity to enhance and demonstrate interoperability and also gain from the best practices in maritime security operations from its partner nations. It has sent to the exercise INS Sahyadri, the third ship of the indigenously designed and built Project-17 class multi-role stealth frigates, and INS Kolkata, the first ship of the indigenously designed and built Project-15A class destroyers.

Both ships have been built at Mazagon Dock Ltd, Mumbai, and are fitted with a state-of-the-art array of weapons and sensors to detect and neutralize threats in surface, air, and underwater domains.

The Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force (JMSDF) has deployed destroyer JS Shiranui (DD-120), part of the 1st Surface Unit of the JMSDF’s Indo Pacific Deployment 2023 (IPD23) mission, along with a special boarding unit of the JMSDF.

The US is deploying destroyer USS Rafael Peralta (DDG-115), fleet oiler USNS Rappahannock (T-AO-204), a submarine, P-8A Poseidon Maritime Patrol Aircraft (MPA), and special operations forces.

Ships from the four nations are being joined by Australian F-35 fighter jets, P-8 surveillance aircraft, and submarines. HMAS Brisbane’s Hobart Class guided-missile destroyer has joined the HMAS Choules, a helicopter and landing craft ship that can carry up to 700 troops from Australia.

In fact, the most important feature of this edition of the MALABAR is that a fifth-generation aircraft (F-35) is appearing for the first time.

It may be noted that both the Indian and Japanese JMSDF stopped at the Pacific island states of Papua New Guinea and Solomon Islands on their way to Australia for the exercise. And this was significant, according to Admiral Thomas.

“The deterrence that our four nations provide as we operate together as a Quad is a foundation for all the other nations operating in this region. Oceania, the island nations that are just northeast of Australia…all of our nations now are focusing on those countries,” Thomas has said.

As it is, though China has not been named, it was obvious that it was China that was in his mind when Admiral Thomas told the newspersons on the eve of the MALABAR exercise at Sydney how he had just visited the Philippines, where last week a Chinese coast guard vessel aimed a water cannon at a small Philippine boat carrying supplies to an outpost in the South China Sea.

“There’s no country that’s more aware of the challenges being faced right now in the South China Sea than the Philippines. We sail quite regularly in the South China Sea as does every one of the nations standing here today,” Thomas said, adding, “Being out there to be able to try to maintain some peace, some stability in that area is important to challenge claims that maybe are not — that are in violation or certainly don’t fall in line with the United Nations Commission Law of the Sea. So you have to have to be there to test those excessive claims. You have to do what the US Navy does, which is freedom of navigation ops to contest those excessive claims.”

It may be noted that Beijing has refused to accept the UN Law of the Sea’s tribunal ruling that China has no legal claim to the South China Sea and has persistently threatened and sometimes attacked the Philippine ships and other nationals operating in what it claims as its waters.

Even India’s foreign office has expressed concerns over the latest Chinese actions against the Philippines. “We’ve always felt that the issues need to be resolved, disputes peacefully, and the rules-based order, and we would certainly urge parties to follow that as well as ensure that such incidents do not happen,” said Ministry of External Affairs spokesperson Arindam Bagchi on August 11. “We have also underlined the need for peaceful settlement of disputes,” he added.

In June this year, while reiterating the call for a free, open, and inclusive Indo-Pacific, India, for the first time, joined the Philippines in asking China to abide by a 2016 legally binding ruling that strongly refuted China’s expansive claims in its dispute with the southeast Asian country over South China Sea waters.

Against this background, it is significant that Admiral Thomas has highlighted that “ MALABAR gives us that capability and that tactical interoperability, to be able to go up there and sail confidently to ensure that a body of water — the South China Sea, which is close to a tremendous amount of trade — stays free.”

In fact, “interoperability” is a cardinal feature of the Malabar exercise. It enhances synergy and coordination, along with interoperability, among the four Quad navies. Various editions of this exercise highlight the convergence of views among the participating countries on maritime issues and their shared commitment to an open, inclusive Indo-Pacific and a rules-based international order.

Vice Admiral Anup Singh (Retd.) of the Indian Navy argues that in perspective, “the Indian Navy has long had a clear vision on treading the gainful path of maritime diplomacy with friendly maritime nations. A core requirement in this strategy is understanding each other’s best practices at sea to strengthen interoperability. This is why we do bilateral and even multilateral exercises.

“These drills have become a foundation for mutual understanding and combined operations in times of necessity. They serve to hone skills, develop mutual confidence, and create an environment to counter the flow of threats and challenges encountered at sea through inclusive and cooperative efforts. Equally important is the aim of engaging other navies in a positive manner and reinforcing their perception of the Indian Navy as a competent, confident, and stabilizing force in the region.”

The Malabar Exercises seem to have strengthened the bond among the four QUAD countries. Every edition has been an occasion to improve inter-coordination and interoperability of their respective tactical, operational skills in an entirely different operational environment.

Participants become aware of each other’s platforms/ weapons and their effective ranges. They understand each other’s drills and procedures by overcoming language barriers. All this helps when they undertake joint steps against a common enemy or join hands in operations like humanitarian aid, disaster relief, anti-piracy, etc.

Above all, the Malabar Naval exercises by the Navies of India, the US, Japan, and Australia in the Indo- Pacific provide a ‘strategic signaling’ to a third country or a group of countries, usually the potential rivals. No wonder why China thinks negatively of them.

And the signaling here is obviously to China, which is seen to be a challenger to the very idea of free and open access to the great blue water domain of the Indo-Pacific.

Source : TheEurAsianTimes