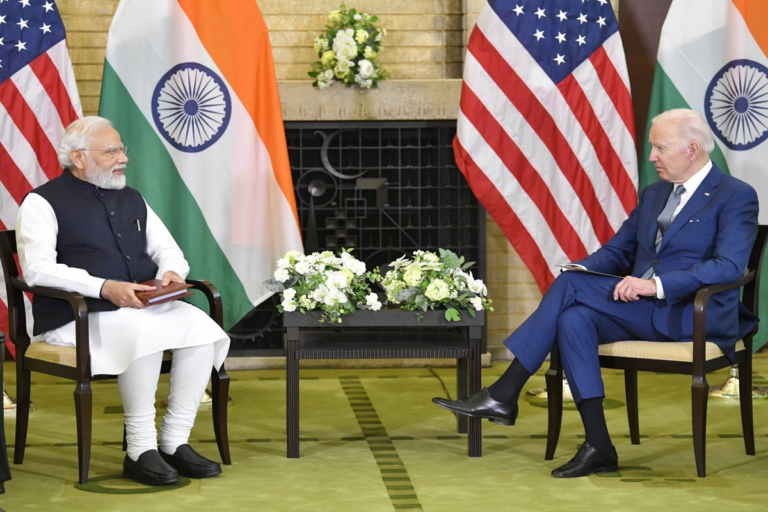

The central theme of the Joint Statement from the United States and India issued at the conclusion of Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s recent state visit to the US was ‘Technology Partnership’. It was around this theme that the two countries inked several agreements involving critical technologies, with the US announcing that it would facilitate the ‘transfer’ of these technologies to India in a number of emerging areas.

The agreements endorsed by the leaders in Washington owe their origins to the initiative on Critical and Emerging Technology (iCET), an initiative for expanding strategic technology partnership and defence-industrial cooperation between the governments, businesses and academic institutions of the two countries.

iCET is intended to promote inter-agency technology cooperation in a number of key areas, including the defence sector, semiconductor supply chains, telecommunications and artificial intelligence.

The most eye-catching among the outcomes of Mr. Modi’s visit was the memorandum of understanding (MoU) between General Electric (GE) and Hindustan Aeronautics Limited (HAL) for the manufacture of GE F414 jet engines in India. This initiative has been projected as one that will enable greater transfer of US jet engine technology to India.

The MoU on Semiconductor Supply Chain and Innovation Partnership was signed with the stated objective of coordinating the semiconductor incentive programmes of India and the US.

Over the past year, both India and the US have focused on enhancing their domestic production capacities of semiconductors. India adopted the modified scheme for setting up domestic semiconductor wafer fabrication facilities under the production-linked incentive scheme, while the US enacted the CHIPS and Science Act with a commitment to spend $280 billion on R&D and commercialisation.

In sync with these developments, the US chipmaker Micron Technology announced that it would invest up to $825 million to build a semiconductor assembly and test facility in India, taking advantage of the fiscal support being extended by the Indian government.

The two countries also launched joint initiatives in telecommunications, and a principally public-private cooperation was initiated in the area of telecommunications on Open Radio Access Network field trials and rollouts between operators and vendors of both markets, with financial support from the US International Development Finance Corporation.

They endorsed an ambitious vision for 6G networks, including cooperation in the critical area of standards, facilitating access to chipsets and establishing joint projects for research and development.

And finally, a $2 million grant programme was launched under the US-India Science and Technology Endowment Fund for the joint development and commercialisation of artificial intelligence (AI) and quantum technologies, with possibilities of public-private collaborations to develop high performance computing facilities in India.

While this is an impressive list of sectors in which the US has agreed to ‘transfer’ technologies to India, the key question is the extent to which the US will meet its commitments. This question arises due to two sets of factors.

The first is that historical evidence tells us that the US has not cooperated with India and other developing countries in making critical technologies accessible. One of the low points in this regard was the reluctance of multinational pharmaceutical companies to allow developing countries to use the technologies for vaccines and medicines during the COVID-19 pandemic.

This stand of the pharmaceutical companies was effectively supported by the US and other advanced countries, especially in the discussions within the World Trade Organisation. Further, developing countries’ access to green technologies has been one of the most vexed issues in climate change negotiations, whose resolution does not seem to be in sight.

A second factor is the fact that advanced technologies from US entities are tagged with a number of conditions, especially those arising from the country’s complex export control regime. These restrictions are imposed on exports of strategic products and technologies to even close allies like Australia and the UK, with whom the US has had long-standing defence deals.

In the joint statement, President Biden tacitly admits the restrictions that India could face in accessing the promised technology, while indicating that his government would work with the US Congress to lower barriers to US exports to India of high-performance computing technology and source code. But the larger problems that the US’ export control regime would impose remain unaddressed.

Before the agreements covering exports of technology to India become a reality, the deals would have to be scrutinised by the US’ export control regime. This stringent regime covers, on the one hand, exports of dual-use goods and technologies, and defence articles on the other. The former is subjected to the Export Administration Regulations (EAR), while the latter are covered under the Arms Export Control Act of 1976, respectively.

The US maintains export controls to protect its national security interests and to promote its foreign policy objectives concerning dual-use goods and less-sensitive military items using the EAR.

These regulations lay down the licensing policy for the covered items and related technologies, which are reviewed by the US government “on a case-by-case basis to determine whether the proposed export or re-export is consistent with U.S. national security and foreign policy interests”.

The EAR covers exports of 10 categories of products and technologies figuring in the Commerce Control List (CCL), and these include electronics design development and production, electronics, computers, and telecommunications and information security, areas that figure prominently in India-US agreements. Detailed procedures are specified for each category of products in the CCL, which, by themselves, can act as a formidable deterrence for the exporters.

The responsibility for regulating, implementing and enforcing dual-use export controls vests with the Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS), an agency of the US Department of Commerce. BIS works closely with foreign governments, industry and trade associations to ensure that exports of dual-use goods from the US remain secure and are in compliance with EAR.

Exports of military items figuring in the US Munitions List are regulated by the Arms Export Control Act (AECA) of 1976, which underlines the US’ foreign and national policy objectives for defence cooperation and export controls of military items.

AECA lays down a slew of conditions on the uses to which these items can be put. It states that military items “shall be sold or leased by the United States Government … solely for internal security, for legitimate self-defence” or “to permit the recipient country to participate in regional or collective arrangements or measures consistent with the Charter of the United Nations…”

Further, as in the case of exports of dual use products, exports of military items are governed by strict licensing policies set out under the International Traffic in Arms Regulations (ITAR). Clearly, the US administration and the Congress exercise considerable control not only over the exports of dual use and military items, but more importantly, they set conditions for the use of these items in the recipient countries.

Two of the US’ closest defence allies, Australia and the UK, have frequently raised concerns over the indiscriminate and extraterritorial application of its regulations. Importantly, the US had signed Defense Trade Cooperation Treaties with these two countries in 2007, and in 2021, a trilateral partnership, AUKUS, was formed between them. And yet, the restrictions on the US’ exports of strategic equipment to its closest partner countries remain undiminished.

In their recent commentary, William Greenwalt and Tom Corben have summarised the problems with the US’ export control regimes in a succinct manner, which, in their view, suffers from two sets of problems.

First, “practical issues relating to inefficiencies in the current suite of export control frameworks and processes”, and two, the “intangible, conceptual issues including the desire for control over innovation, as well as … a “superpower mindset” rooted in a bygone era of strategic and technological dominance …”

Therefore, can India succeed in securing the critical technologies and products from the US when Australia and the UK have failed?

Source : TheWire